One of the most important parts of the robot is the chassis. This piece ties all of the components together, and determines many of the operating characteristics of the robot. Behind every successful robot is a meticulously designed chassis, oftentimes custom-built for the purpose. Sometimes, you can get lucky and piggyback off of someone else’s design, using a pre-built chassis. However, most of the times these pre-designed chassises are too expensive or unsuitable for the task the robot is to perform, so a custom-built chassis is required.

When custom-building a chassis, one of the first decisions to make is the material of the chassis. There are lots of materials out there that can be used as a chassis, but there are four that are pretty popular: wood, 3-d printed plastic, acrylic, and metal. Which one to choose? That depends on the requirements. In this post, we will take a look into the factors to keep in mind when choosing between these materials.

Wood

I can feel most of you rolling your eyes at the suggestion that wood be used for a chassis. A hunk of cedar certainly doesn’t seem to fit the definition of “high tech” - but, as it turns out, wood is one of the best materials to use for building a robotic chassis! Wood sheets are available in many different sizes, from small sheets of plywood to giant bars used to build houses. There are also many different types of woods: there are “soft” woods like MDF that are made from wood fiber and wax, to “hard” woods like cherry and oak. Choosing wood for a chassis has many benefits:

- It is very easy to get. A quick trip to the hardware store will yield many different kinds of woods, from thin sheets of plywood to thick support bars.

- It is very cheap. A 2x2’ sheet of MDF runs ~$2 at my local Home Depot. Of course, exotic woods like cherry can be expensive, but usually these are not of interest when designing robot chassises.

- It is very easy to work with. No specialty tools are needed to cut or drill holes into wood, making it extremely easy to custom-mount parts. And if you happen to drill too many holes, then just head to the hardware store and pick up another piece of wood. If you do happen to have more expensive tools (like a drill press or a laser cutter), then chances are it will work fine with wood as well as other materials.

- Although wood is not waterproof out of the box, it can be waterproofed with a $5 can of sealant.

In summary, wood is cheap, abundant, and easy to work with. What’s not to love? Turns out, a few things:

- Inconsistencies in the wood can make it difficult to mass produce. For example, choosing to make a base out of a sheet of plywood can cause trouble when you start getting warped sheets or sheets with knots in it. It’s easy to go to your local hardwood store and find one perfect sheet that isn’t warped for a prototype, but much more difficult to find 100 for a production run.

- Wood doesn’t handle dynamic loads well. If your robot has lots of heavy moving parts, it can break the wood chassis.

- Wood isn’t suited for long exposure to water. While it can be waterproofed, it has the potential to warp if exposed to water for long periods of time.

- Wood deteriorates with age much more rapidly than other materials.

- Wood certainly doesn’t have the high-tech aesthetics of other materials. While it can be made to look decent, it will never have the “wow” factor of a metal or acrylic bot. Depending on the purpose of the robot, aesthetics can be a non-issue or it can be an important design consideration.

- Wood doesn’t conduct heat well at all. Don’t try using your chassis as a heat sink, or it may go up in flames.

So, where should wood fit in the toolkit of a chassis designer? In my view, wood is the ideal prototyping material for one-off chassises. It is great for getting a first or second iteration out of a design, as its ease of use and relative abundance mean easy recovery from early mistakes. It’s also relatively easy to answer questions like “what happens if we relocate this component on the robot,” which is a vital part of the design iteration process. Wood should probably not be used for robots that spend a significant amount of time in the water, robots that need to handle heavy weights, or robots where the

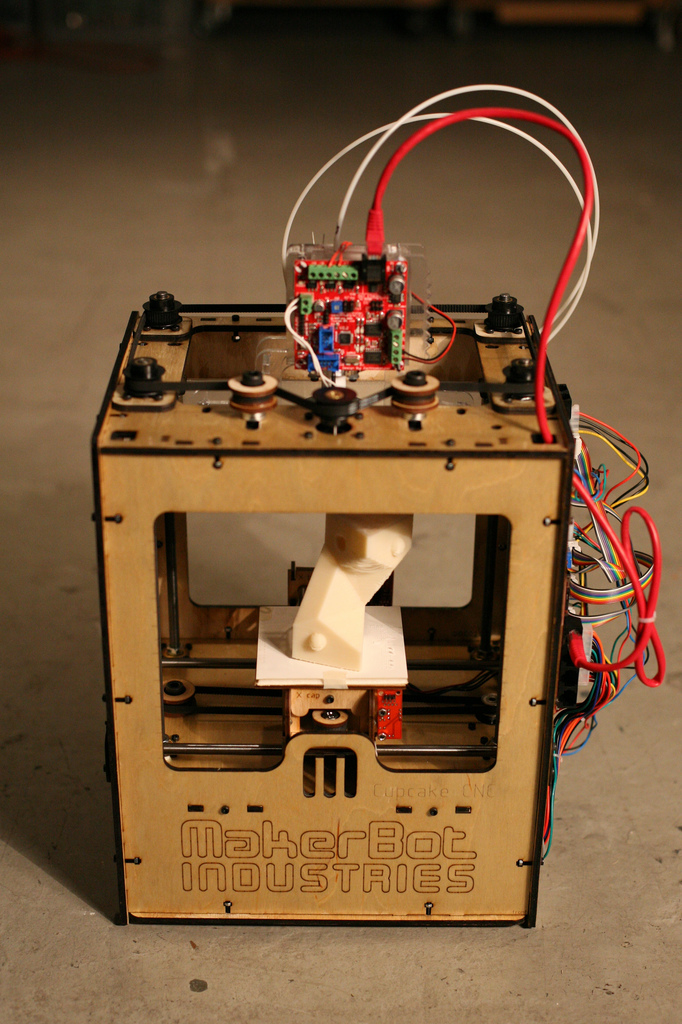

3-d Printed Plastic

3-d printing is one of the hottest new technologies. The idea is that you draw up your component in a CAD system, export the model to the printer, and click “print.” A machine then heats up plastic and extrudes a thin stream into a pattern, building your part from the ground up in a series of thin layers. The most popular materials for 3-d printed parts are Polylactic Acid (PLA) plastic or Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) poastic. Of the two, PLA is more forgiving to work with, but ABS generally produces a stronger print that is more resistant to thermal fluctuations. There’s a few benefits to using a 3-d printed chassis:

- Because you model your chassis in software before printing, it is easy to make changes before actually clicking the “print” button.

- It’s possible to get extremely precise features printed.

- It’s possible to make parts that are exact duplicates of each other, as each time the “print” button is clicked, an identical copy gets printed.

- 3-d printed parts with standard materials (PLA and ABS) are waterproof.

Unfortunately, there are many drawbacks as well:

- 3-d printers are expensive. In addition to the initial start-up costs (which can run from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars), you need to purchase filament for every print, which is not cheap.

- 3-d printers are difficult to maintain. Unless you can get the part printed professionally or have experience running a 3-d printer, you can end up spending countless hours debugging failed prints due to improper nozzle temperatures, improper bed heating, etc.

- Finding filament for a print can be difficult. Online retailers supply the stuff, but it usually takes a few days to ship. This is becoming less of an issue, as more modern retailers (such as Fry’s Electronics) start carrying 3-d printer materials, but filament is still more difficult to come by than other materials on this list.

- 3-d printers have a relatively small build volume (many low-end printers have about a cubic foot of build volume). If your chassis is larger, then you need to print in multiple pieces and assemble, which is painful and error prone.

- Even if you can fit your chassis within the build volume, you are still subject to bad prints. The part can warp, wasting expensive filament.

- The parts produced are usually weak in at least one direction (the printing direction). This could be a problem depending on the loads you need to put on the chassis.

- 3-d printing is not particularly swift. While printer technology is always improving, it can still take hours to print a part. This slows down the iteration speed greatly, making it painful to make changes.

- 3-d printed parts are generally not thermally conductive. The plastic will re-melt if too much heat is dumped into them.

So, where does this leave 3-d printing? I’d say that except for very small robots, it would be better to look elsewhere for a chassis material. Does that mean 3-d printing is useless in robotics? Absolutely not - it’s just better suited for smaller parts, which mitigates many of the drawbacks of the technology. For large parts like a robot chassis, you may want to look at another material and manufacturing method.

Acrylic

Thick sheets of acrylic plastic are beautiful to look at, and they make great chassises for small to medium-sized robots! There’s a lot to love about acrylic-based materials:

- Acrylic looks awesome! When properly machined, acrylic gives nice, clean edges and a high-tech look to your robot. In addition to looking great, acrylic also has the benefit of being clear. This allows you to see inside of your robot, making it easier to check on the internal electronics of your bot (i.e. via status LEDs).

- Acrylic is strong. When purchased in thicker sheets, acrylic can take some serious weight. Not as much as various metal alloys (more on that later), but it is definitely more sturdy than 3-d printed parts or wood parts.

- Acrylic is waterproof and can handle the elements well.

There are some drawback to Acrylic-based chassises:

- Acrylic can be somewhat expensive. For example, Tap Plastics lists a 1/4” thick sheet of clear acrylic at $10 / sq foot. For a larger robot, this can add up quickly.

- Acrylic can be heavy, especially in thicker quantities or for larger robots.

- To get the most out of acrylic, you will probably want to use specialized tools to cut the plastic, like a laser cutter. Otherwise, it’s easy to scratch or crack the surface.

- Sheets of acrylic can be hard to find. Sometimes, hardware stores sometimes carry sheets of acrylic, but the selection is usually limited. It can be ordered online, but then you’re waiting for shipping times.

- Acrylic is not thermally conductive, although it is much more resistant to heat than 3-d printed or wood chassises.

Where does this leave acrylic? Acrylic is a good material for a small to mid-sized robot where aesthetics are important. In addition, it is a good material when specialized cutting equipment is available, and when the robot needs to be able to handle small to medium sized loads. Acrylic is too expensive to use for rapid prototyping, however, so it should generally be reserved for final iterations of a design.

Metal

Finally, we get to the material that most people think of when people say “robot.” If one of the above materials does not fit your use case, then you have no choice but to use a metal chassis. Metal chassises are generally stronger than chassises made out of any of the other materials, which makes them great for heavy-duty robotics. They are more difficult to work with and use than other materials, however. There are too many different metallic alloys that are out there to discuss in one article, so I will limit the focus to two of the most popular types used in robotic applications: aluminum and stainless steel.

Aluminum

Aluminum is the 13th element of the periodic table. In its pure state, aluminum is quite soft, so for most uses, it is combined with other metals in an alloy. One of the most popular alloys is 6105 aluminum, which is about 97% aluminum, with iron, copper, titanium, and a few other metals mixed in for strength. Aluminum is a popular choice for many robotic chassises for a few reasons:

- Aluminum is one of the lighter metals, decreasing the overall weight of your robot. This may be important for your application, or it may be inconsequential.

- Because aluminum is used in a lot of robots, there are already a lot of companies making pre-machined aluminum parts that are useful for robotics, reducing the need for manual machining. This can make your bot quicker to put together. An example would be the [80/20 extruded aluminum bars](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/80/20_(framing_system), which consist of slotted aluminum bars with inserts allowing bars to be connected at right angles without any machining. These pieces are generally more expensive than standard shapes (such as aluminum tubes), but can save lots of time when building the robot.

- Aluminum is a softer metal, making it easier to machine with hand tools like drills and saws.

- Aluminum handles the elements well. That is, it won’t rust.

- Of the materials on this list, aluminum is the best conductor of heat.

There are a few drawbacks to using aluminum, as well:

- Aluminum is a softer metal, which means that it can’t take quite as high of loads as steel.

- Per pound, Aluminum is generally more expensive than steel.

- Aluminum is notoriously difficult to weld. In fact, if welding is a requirement, that may be grounds for dismissing Aluminum altogether.

Steel

Unlike aluminum, steel is not an element in the periodic table. Instead, it is an alloy primarily composed of iron, with some other metals such as aluminum, chromium, and copper mixed in. In addition, steel contains a small amount of carbon, which increases the strength of the metal. Steel is often chosen because it does not have many of the weaknesses of aluminum:

- Of all of the materials considered, steel is the hardest and strongest material for building your chassis. If you are expecting your chassis to take a lot of abuser or if your chassis needs to handle very heavy loads, then steel is your optimal material.

- Steel is relatively cheap when purchased in quantity.

- Steel is thermally conductive, allowing the chassis to be used as a heat sink. It’s not as conductive as aluminum, but it can still be used quite nicely.

- Welding steel is pretty easy, compared to aluminum.

However, steel does have some drawbacks as well:

- Steel is heavy. Very heavy. This can have a snowball effect during the design phase in which you need larger motors or actuators to move your robot. This can require extra steel to support and secure the heavier components, causing the robot’s weight to balloon.

- Steel is a hard metal, making it difficult to machine with hand tools.

- Steel will corrode unless treated, so it is not waterproof out-of-the-box.

So, in summary, metal is a good choice if you have a large robot or a robot that has to take a beating. Aluminum is a great choice except when the robot needs to handle very heavy loads, in which case steel should be used.

Summary

In this article, we’ve taken a deep dive into a few different materials used to make robot chassises. We’ve examined the strengths and weaknesses of each of the different materials, and come up with a rough intuition for when each should be used. Wood is a great material for prototyping and one-off work, but it doesn’t perform well under heavy loads or for mass-produced parts. 3-d printed chassises should be avoided for all but the smallest robots due to its cost. Acrylic is a great choice for the final iteration of a small to medium sized robot that doesn’t need to take heavy loads, as it is strong and looks sharp. Aluminum should be used for larger robots or those which need to deal with moderate to high loads. Finally, steel is a good choice for robots that need to handle heavy loads, but comes at the price of weight and ease of use. Also, keep in mind that all of these rules are just guidelines. In the right circumstances, almost anything can be a chassis. For example, in this project, I turned an orange plastic home depot bucket into a robotic chassis!

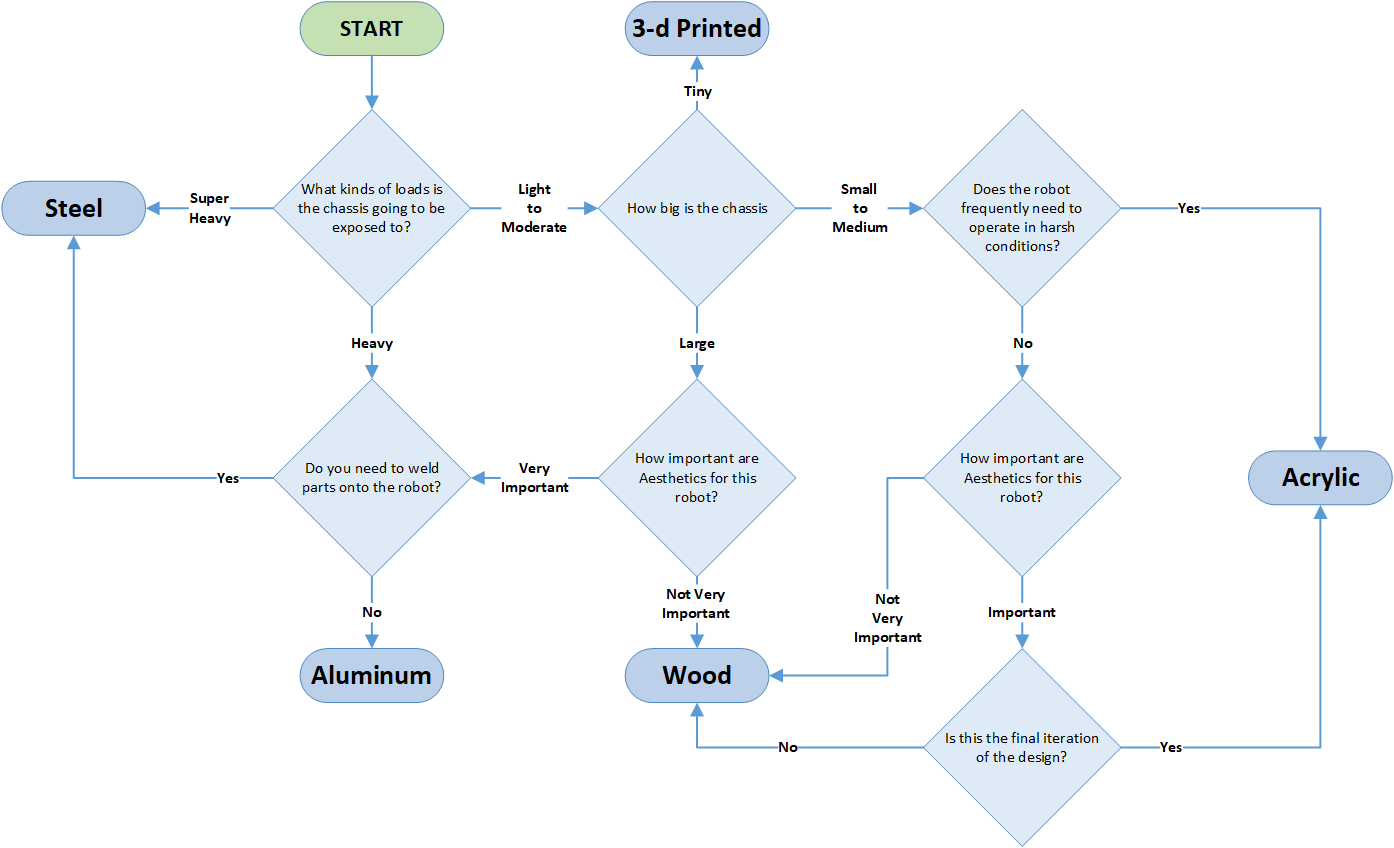

To summarize all of this information into a concise document, I’ve made a flowchart. This can be used to help plan out which chassis material to use when prototyping your next robot. For this flowchart, I highlighted the one or two most important things that I usually consider from the lists above. In addition, I assume that all of the tools are available for working with the material chosen. Click on the image to enlarge it.

What materials do you all use when making your robots? Let me know in the comments below!

So many options, I would think also from a Steampunk or vintage vantage whereby something is repurposed to give it a new life.