As humans begin to explore deeper into space and mission times become longer, the cost of transporting vital supplies such as fuel, water, and food become prohibitively expensive. Accordingly, one of the concepts being researched at NASA is “in-situ resource utilization.” Essentially, instead of carrying all of the supplies that are needed for the entire mission, only enough supplies needed to reach the destination are loaded onto the shuttle. Once at the destination, be it an asteroid, planet, or some other celestial body, the natural resources of the destination will be used. If this process can be achieved, then the creation of a self-sustaining colony on another planet enters the realm of possibility.

One of the preliminary steps necessary for in-situ resource utilization is the ability to mine and transport the surfaces of these extraterrestrial planets. In addition to being able to mine and transport the extraterrestrial soil, or “regolith”, the machines used for mining must be able to operate autonomously, to some extent. Because of the vast distances between planets, there is a significant delay between sending a command from Earth and the reception of the command on another planet. Therefore, the mining machine must be able to navigate, mine, and offload with minimal human intervention for maximum safety and efficiency.

Originally a millennial challenge, the annual NASA Astrobotics challenges teams of college students to design and build a mining robot that can operate on another planet. Every year, a week-long competition is held at Cape Canaveral in which the teams bring their robots and test them out in pits of “BP-1”, or simulated regolith. While there are various awards, the two most coveted awards are the on-site mining award and the Joe Kosmos award for Excellence. The on-site mining award is awarded to the teams that accrue the most points during the competition test runs. Points are awarded for the amount of regolith mined, the dust tolerance of the robot, and any display of autonomous operation. Points are deducted based upon weight and bandwidth usage. Due to the complicated scoring system, the design process is full of tradeoffs - do you build a robot that is heavy and can mine a lot of regolith but takes a heavy weight penalty, or a small, light robot that can’tmine much but doesn’t have a heavy weight penalty? Every year the rules are tweaked, to make the competition more difficult and more realistic.

The Joe Kosmo award for Excellence is the most coveted trophy awarded at the competition. Like the on-site mining award, teams are awarded points, and the highest score gets the trophy. Unlike the on-site mining award, however, the Joe Kosmo award for Excellence takes more into account than your mining score. In addition to the mining score, teams are judged based upon a paper detailing their design process (“systems engineering paper”), an optional on-site presentation detailing their design process, and a few other categories such as “team spirit” and “social media usage.”

I have been a part of the team for four years, and in my tenure as a software developer, I have seen the team grow tremendously, from the 2011-2012 design cycle, in which the team consisted of nine members, to the 2014-2015 design cycle, in which the team consisted of over 35 members! Every year, the competition gets tougher; the robot that won the on-site mining competition in one year will not place in the top ten in the next. Pictured below are the robots in which I have had a hand in bringing to competition.

This robot, the MOLE 1.0, was the University of Alabama’s entry into the 2011-2012 competition. This robot consists of two parts - a “base” module and a “digging” module. One of the common themes of the designs from the University of Alabama is this modularity - the base can be separated from the module and keep working. This allows a single base to be designed and used for multiple modules. For example, if one wanted to build a reconnaissance module, they could re-use the base design and simply design a new module. This cuts down on design time and the number of parts that would need to be sent to an extraterrestrial colony.

In addition to the modularity, the other interesting feature of this bot is the swept wheels. In this design, the wheels can sweep from the side of the bot to the front, and anywhere in between. By moving the wheels halfway through their range of motion, the bot can perform a “zero degree” turn. This type of turning puts much less stress on the motors than a traditional skid steer, allowing for smaller, lighter motors to be used.

The MOLE 2.0, was the University of Alabama’s entry into the 2012-2013 competition. This robot is an updated version of the MOLE 1.0, with two major changes. First, the electronics are housed in 3-d printed parts, which cut down on weight while still maintaining the robustness towards dust of the previous design. In addition, a second digging head was added in order to increase the amount of regolith that could be mined on each digging cycle. In practice, the addition of the second bucket made offloading a challenge, leading to the removal of consideration of this robot from future designs.

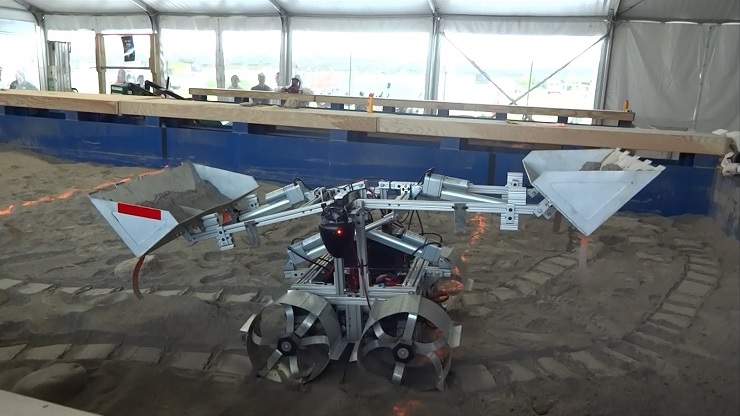

The MARTE 1.0, signified a change in mindset from the previous years. In the MOLE bots, the base was constructed from extruded 80/20 aluminum. While this made fabrication simple, the extruded aluminum was heavy. The MARTE 1.0 features a welded aluminum base, which trades robustness for weight. The robot maintained its modularity from previous years; the base can function fully independently from the module. In addition, a bucket-chain design was explored for this mining cycle.

One of the most exciting innovations with this robot was the autonomous capabilities. In addition to the base and digging modules, there was also an “autonomy” module integrated into the system. This system consisted of a LIDAR, a camera, a pan/tilt gimbal, and a single-board computer. This single-board computer would use the sensors to determine the robot’s position, and then guide it through the mining cycle. The system was able to determine the robot’s localization by identifying the walls of the arena in a 2-d LIDAR scan, then using the locations of the corners to triangulate the position. This is quite a difficult task; the University of Alabama was the only team that was able to detect and avoid obstacles, cross to the digging area, and offload in a competition run.

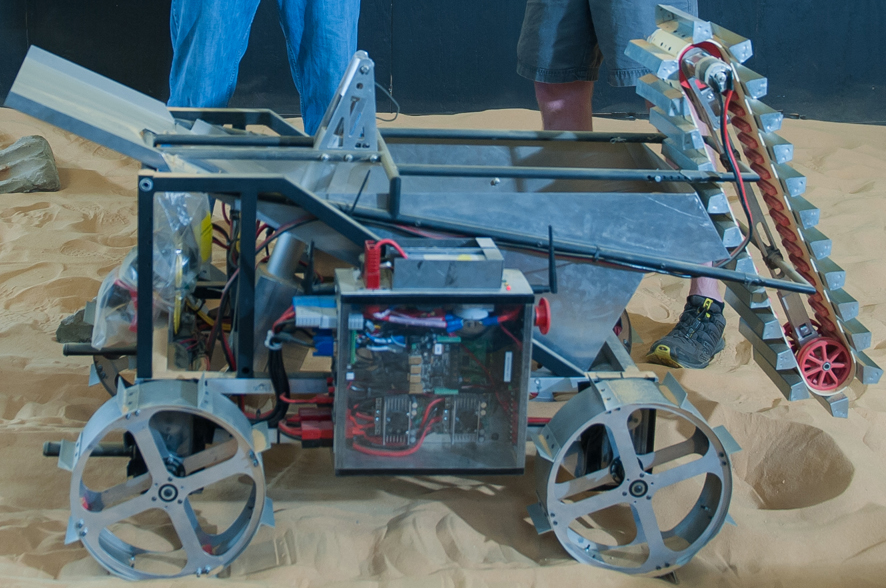

This robot, the MARTE 2.0 is the latest submission to the competition from the University of Alabama. Mechanically, it is similar in design to the MARTE 1.0; the goal of this year was to cut weight from the robot. In that respect, the design cycle was a success - there was approximately a 50% weight savings from the MARTE 1.0. In addition, this robot was able to operate fully autonomously utilizing only a paper beacon hung on the offloading bin. This makes the strategy more applicable to lunar missions - there are no walls on the moon!

In my four year tenure with the program, the University of Alabama has been awarded the Joe Kosmos Award for Excellence three times (to be fair, there is a bit of controversy about one of the years, but we did receive the award three times), and has won the mining award once. For reference, there are generally between 50 and 60 teams at the competition each year from around the world. In addition, we have a very good record in the other miscellaneous awards, having received awards for the on-site presentation, systems engineering paper, team spirit, and our K-12 outreach program.